Investing Newsletter 5.23

April 2023 economic,market and policy update

The economy

A record 69 percent of respondents to a recent survey are down on the economy. [1] At first blush, this is puzzling. Many measures of economic health, such as employment and spending, are strong on the surface. But the economy’s direction can change quickly, and there are some signs of trouble ahead.

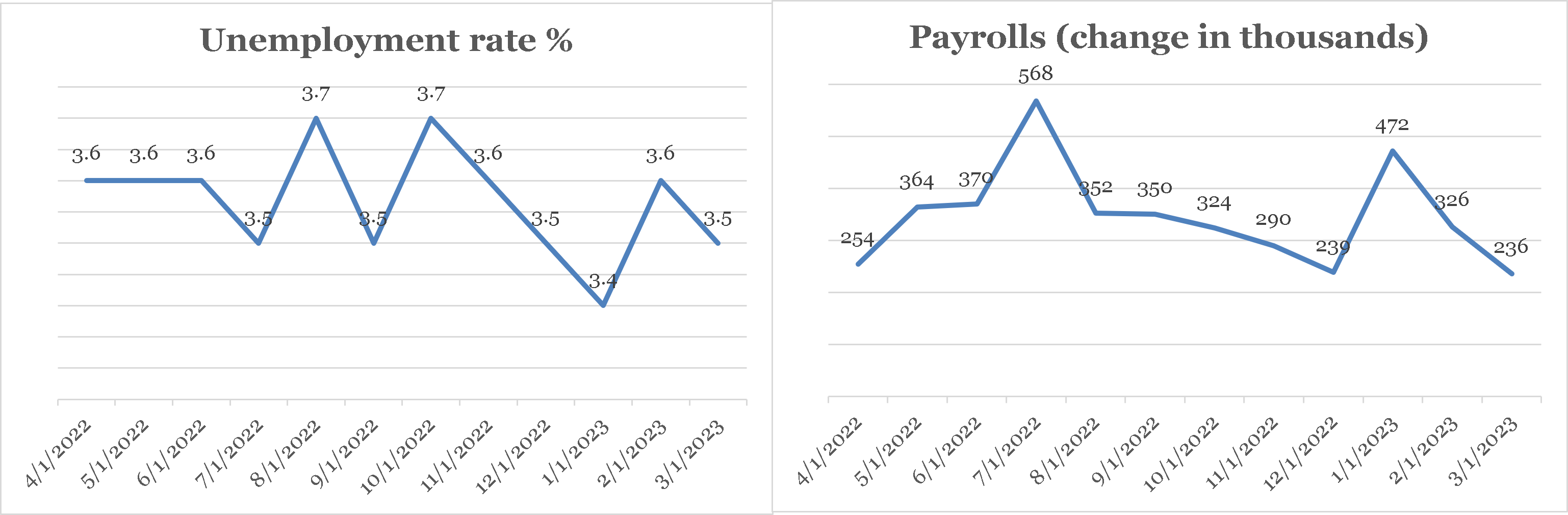

The labor market is operating at full or above-full strength: in April we learned that unemployment rate, or the number of unemployed people divided by the size of the civilian labor force, remains at its lowest levels since the 1960s, and job creation is more than enough to make up for labor force growth. [2] But these are lagging indicators: they tell us about the past, not the future.

The unemployment rate is 3.5 percent (left panel), and an average of 314,000 new jobs were created in the last six months (right panel).

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve

CLICK ON CHART TO VIEW LARGER IMAGE

Measures more helpful for forecasting point to some softening in the job market. The number of job openings reported in April (for February) fell for the third straight month to 9.9 million from a high of about 12 million last year. And the four-week average of new unemployment claims, a leading economic indicator, remained elevated in April (236,000) after jumping in March relative to February. If these trends continue, labor market easing may reduce pressure on wage growth, and thus on price growth.

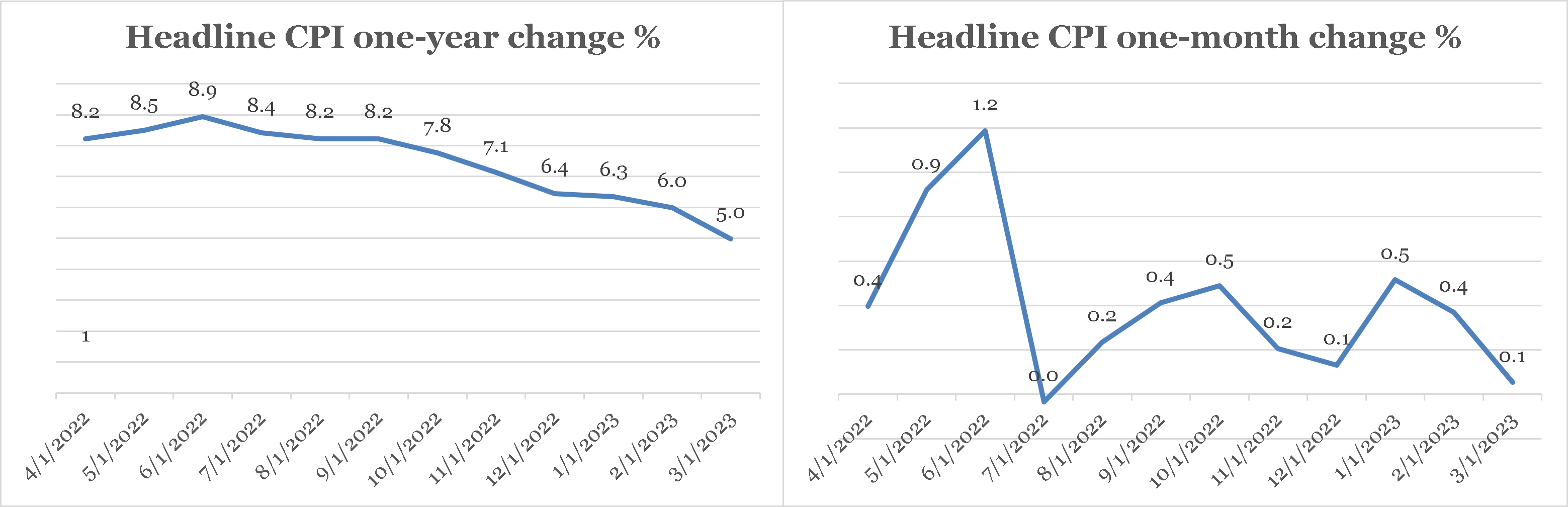

Inflation is the increase in the average price of goods and services in the economy. And in April we learned that the year-over-year rate continued to fall due to a slowdown in monthly growth rate of prices.

Year-over-year headline inflation has slowed to 5 percent (left panel) thanks to a string of moderate month-over-month changes (right panel).

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve

CLICK ON CHART TO VIEW LARGER IMAGE

Core inflation, which takes out food and energy prices to avoid reading too much into their jerky short-term movements, rose 0.4 percent month-over-month. This is about the same clip as the last several months. By this measure, prices are no longer soaring, but they aren’t dropping quickly either.

No one knows if headline inflation will continue to subside, level off, or tick back up. One sign confirming easing price pressures can be found in the labor market: the three-month average of the average month-over-month increase in hourly earnings, currently 0.26 percent, has fallen steadily for the past several months. Another is that economic growth (gross domestic product or “GDP”) slowed in the first quarter to an annualized, real (after-inflation) rate of 1.1 percent after growing by 3.2 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively, in the third and fourth quarters of 2022. Consumer spending continued to push GDP higher, as it has in every quarter since the COVID recession ended in early 2020. Business investment and inventory drawdowns held growth back.

A potentially unhelpful sign for inflation is that housing prices, as measured by the Case-Shiller national home price index, rose by 0.2 percent month-over-month (in February, reported in April) after declining in each of the previous seven months. Since 2020, home prices are up 38 percent (versus 17 percent for prices overall). Since shelter costs make up over a third of the CPI, any meaningful reduction in inflation will probably require a prolonged and gradual (or short and steep) decline in house prices. Also, housing starts rose in March (reported in April) for the third straight month. A possible pickup in housing may be good economic news but likely won’t help to get inflation down.

Overall, economic signals were mixed in April. The economy is strong by some measures, though its growth rate is likely slowing. That same overall strength is keeping inflation well above the Federal Reserve’s (Fed’s) 2 percent target despite recent easing. These mixed signals gave stock and bond investors little to go on in April..

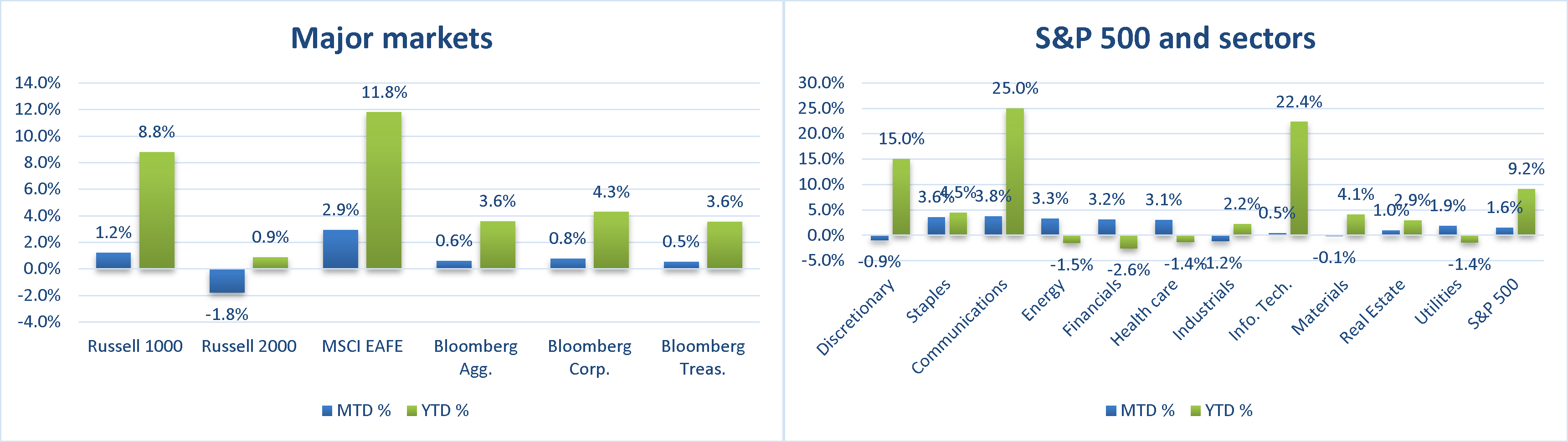

Financial markets

The broad U.S. stock market as proxied by the S&P 500 index of large U.S. companies gained 1.5 percent in April, increasing its year-to-date return to 9.2 percent. [3] The year’s best-performing sector, communications (+25 percent, year-to-date), was also among the month’s best performers (+3.6 percent in April). The year’s worst-performing sector, financial services (-2.6 percent) boosted returns in April (+3.2 percent) as well, as fears of bank-failure contagion moderated. The U.S. bond market, as measured by the Bloomberg Aggregate index, gained 0.61 percent in April, probably boosted by fears over slowing economic growth (see above). Slower growth generally supports bond prices and lowers yields. The sense that the Fed was nearing the end of its interest rate hiking campaign (see below) may have also boosted bond prices.

Foreign companies (the MSCI EAFE index) were the best performers among major asset classes (left panel), while utilities and consumer staples stocks led U.S. markets (right panel)

Source: Data provided by Russell Investments, Morgan Stanley Capital International, Bloomberg and Standard & Poor’; returns calculated by YCharts.

CLICK ON CHART TO VIEW LARGER IMAGE

While first quarter 2023 corporate earnings have largely exceeded expectations—data provider FactSet reports that about 80 percent of those reporting have surprised to the upside as of May 1—profits are down roughly 6.2 percent year-over-year, the largest drop since early 2020 and the second consecutive year-over-year quarterly decline. This could explain why strong earnings results haven’t translated into better stock performance. Additionally, stocks remain “expensive” relative to long-term earnings in historical terms. The ratio of the price of the S&P 500 stock index to long-term average real earnings—a measure of how expensive stocks are today compared to their history—is in the top 5 percent of its historical range. This may mean that investors were already expecting strong earnings and continued economic growth. In the absence of earnings or economic surprises, capital markets had little reason to move much. This may not be the case in the months ahead, however, as the Fed and policymakers are faced with crucial policy choices.

Economic Policy

The Fed’s monetary policy committee didn’t meet in April. But when it convenes in the first week of May, “futures” markets put about 90 percent odds on a 0.25 percent increase in its target “Fed funds” interest rate as of May 1. [4] That would bring Fed funds to 5 percent. Is that enough to get inflation back to the Fed’s two percent target? The answer depends on inflation itself and the “neutral” (or “natural”) rate of interest.

Most economists think that, for inflation to return to 2 percent, the real (after-inflation) Fed funds rate must exceed the neutral rate. The trouble with this concept is two-fold. One, no one knows exactly what inflation is right now—we know what it was last month or last year, but not what it will be this month. And two, the neutral rate is a guess. A reasonable estimate is 0.5 percent to 1.3 percent. [5] And a reasonable estimate of the true rate of inflation is around 4 percent. Using these estimates the real Fed funds rate will be positive 1 percent, assuming the Fed hikes in May as anticipated. And this will might be slightly above or slightly below the neutral rate of interest.

If inflation continues to fall, then the real Fed funds rate will continue to rise—even if the Fed does nothing. But if inflation doesn’t continue to fall, then the real Fed funds rate may not be high enough to reduce inflation further. Unfortunately, we won’t know whether the Fed did too much, not enough, or just the right amount of tightening until after the fact.

Meanwhile, Congress and the Biden Administration remain at loggerheads over increasing the borrowing authority of the U.S. government (the debt ceiling). The Republican Congress is demanding spending cuts that a Democrat Senate and Administration won’t consider. While we are optimistic that a U.S. government solvency crisis will be averted, as it has on several occasions in the last 15 years following similar brinkmanship, uncertainty over exactly how and when could roil capital markets in the interim.

Article endnotes appear at bottom of newsletter.

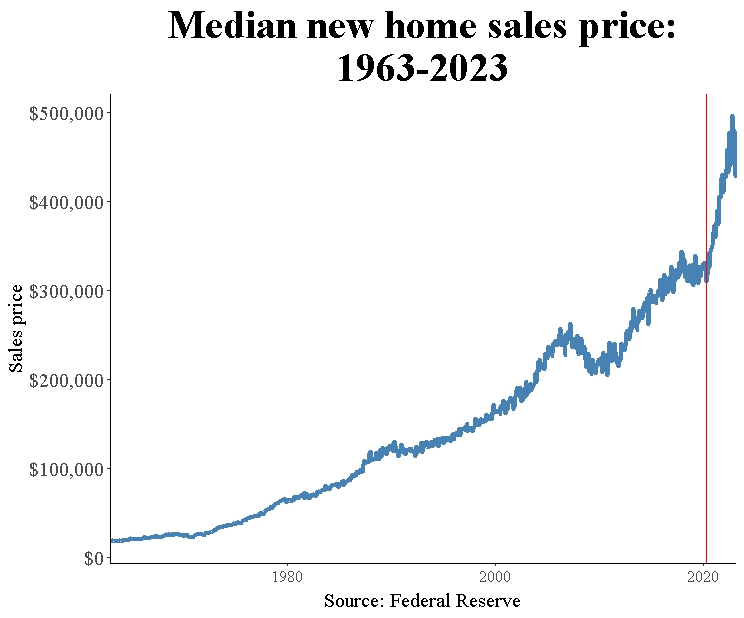

Why Home Prices Matter

The median (middle) new home sales price has fallen about 9 percent from its mid-2022 peak. [6] Despite this pullback, price gains since the end of the last recession in April 2020 have been remarkable. In the last three years, the median new home price grew by about 45 percent. The same-sized gain took almost nine years to achieve following 2007-9 recession, or almost three times as long.

Home price changes are of interest for three reasons. One, retirement savers may be counting on home equity to finance expenses after they stop working either through selling or borrowing against their home’s value. Two, home building (residential construction) is an important part of investment, which is in turn a large contributor to the growth of the economy. And three, spending on home furnishings and equipment is an important component of overall spending and is thus also a key driver of economic growth. So, the direction of home prices has potentially big implications for the economy—and therefore for stock prices.

Must what go up come down?

The dramatic growth in home prices compared to growth in prior periods is apparent from the chart below, which shows the change in the median sales price of new homes for the last 60 years. The spurt beginning at the beginning of the current expansion, highlighted with a red vertical line, is unmatched by any other increase in terms of steepness (rate of growth) since records began.

Source: Federal Reserve

CLICK ON CHART TO VIEW LARGER IMAGE

Researchers offer several reasons for the dramatic change in the growth rate of homes since early 2020 such as: a switch to remote working, pushing up demand for homes outside of typical commuting ranges; “millennials” entering the market for homes in large numbers, pushing up demand generally; low mortgage rates, making monthly home payments more affordable; and changing preferences for home ownership, among other rationales. [7]

Some of these factors have gone from tailwinds to headwinds, however. Thirty-year fixed mortgage rates have increased by nearly 2.5 times to 6.3 percent since hitting a modern era low of 2.6 percent in late 2020. And remote work may have peaked. [8] While remaining drivers of home prices could provide support, home prices remain high by some “fundamental measures.”

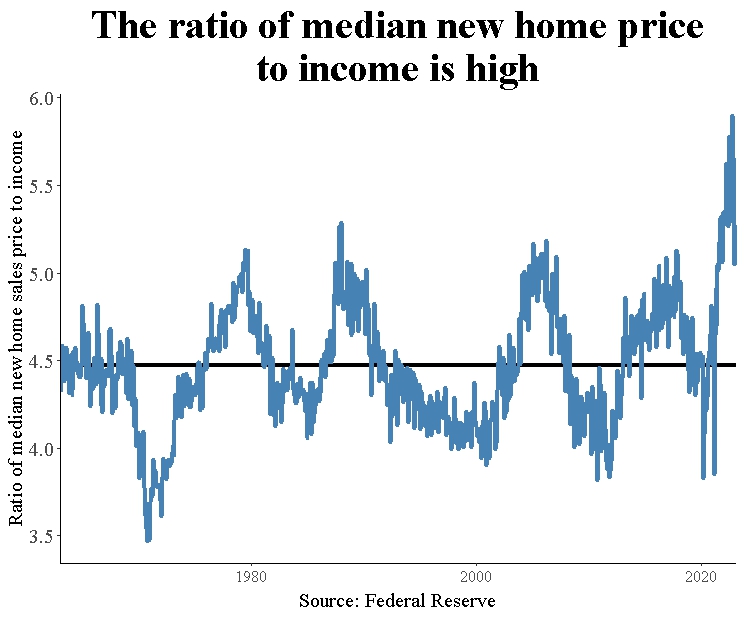

As an example, take home prices compared to income. The chart below shows the ratio of the median sales price of a new home to average income from all sources (total income divided by the noninstitutional civilian population). This measure is “fundamental” because it compares what people pay for homes to their ability to afford them. For decades it oscillated between roughly 4 on the low end and 5.2 on the high end—including during the housing “bubble” of the late-1990s to mid-2000s. This “range-bound” behavior makes sense: in theory, homes should not get too expensive, or too cheap, relative to what people earn (from all sources). But in 2020, this ratio rose beyond all experience, reaching 5.9 in late 2022 before returning to the high end of its historical range recently.

Source: Federal Reserve

CLICK ON CHART TO VIEW LARGER IMAGE

By this measure, homes have become cheaper compared to income. But they could become cheaper still—either by falling outright, or by rising less than income.

Home price changes and the economy

If home prices fall further, the resulting slowdown in activity could sap economic growth in two ways. One, residential construction (private residential fixed investment) is currently about 4 percent of the total output of goods and services (GDP) in the United States. When construction falls, other components of GDP must rise to prevent overall growth from stalling. If they don’t, growth contracts potentially leading to recession (a broad-based decline in economic activity). And two, spending on household durable equipment (e.g., appliances) and furnishings currently amounts to about 3 percent of overall spending. This may not seem like a lot, but total spending is a big chunk of GDP—so a modest change in even a small component of spending can have an outsized impact on overall economic growth. As the end of 2022, private residential fixed investment was 9.3 percent lower than a year earlier, while spending on household durable equipment and furnishings fell to 5.7 percent year-over-year (before inflation) from 12.3 percent year-over-year in 2021. All effects considered, we estimate that a 1 percent fall in all home prices—new and existing—is associated with a 0.1 percent to 0.2 percent decline in economic growth, holding other influences constant. [9]

The future may not be like the past

The jump in home prices since the end of the 2020 recession is unprecedented in speed and magnitude. To the extent that the increase is due to a change in favorable fundamentals, such the attractiveness of owning a home compared to other housing options, home price growth might resume. But with rising interest rates and an growing economic uncertainty (see first article), new home prices may grow very little if at all, on average, over the next several years. Anyone factoring future home prices into their retirement, personal investment, or business investment plans should keep this possibility in mind.

<em>Article endnotes appear at bottom of newsletter.</em>

The Sometimes-Surprising Behavior of Stocks During Recessions

Economic growth might be slowing after a strong start to the year (see first article). Always present recession concerns are growing louder. Yet, the U.S. stock market (the S&P 500 index) has increased by 9.2 percent, year-to-date, through April 30. Can stocks hold up if the economy begins to sputter? History suggests, perhaps surprisingly, that they might.

We talk often about stocks as a suitable long-term investment for an investor seeking growth. In the 20 years ending March 31, 2022, for example, the S&P 500 index of large U.S. companies (stocks) returned 10.4 percent annually. And just so you don’t think we’re cherry picking 20-year periods, in only one 20-year period since records began in 1871 according to a slightly different measure of the performance of U.S. companies was the average annual real (after-inflation) total return on stocks negative—the period ending in June 1921 when stocks returned -0.22 percent, on average, in the preceding twenty years. [10] The average twenty-year return from 1871 to 2022 was 6.6 percent, after inflation. The long-term, wealth-building power of stocks has been remarkable.

Stocks and economic growth

The reason for this is that U.S. economic growth since the late 19th century—like that of other developed, mostly democratic countries around the world—has also been remarkable. Although the government doesn’t provide GDP records prior to the first quarter of 1947, since that time the real economy has increased by a factor of 10, or about 3 percent a year. Public companies, like those that comprise the S&P 500 index, participate in economic growth through rising sales and profits, which are passed along to their shareholders (people who own stocks). Stock returns are thus tied closely to economic growth.

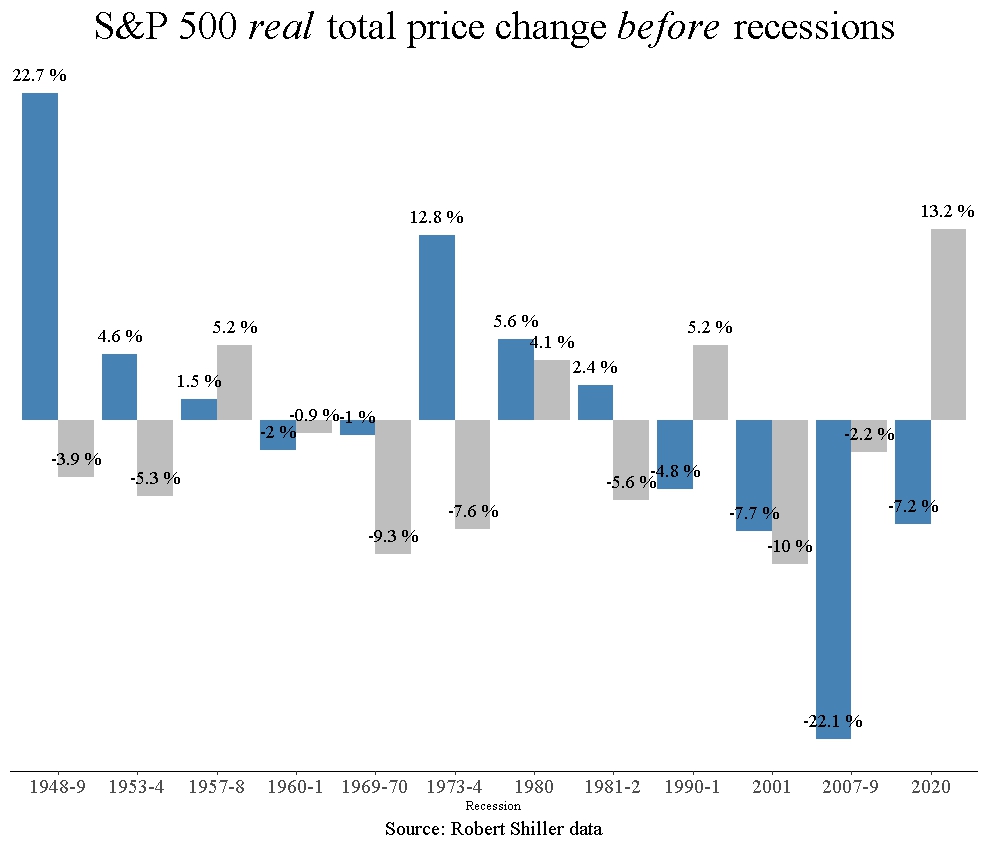

But when that growth slows or, worse, reverses, stocks can suffer. When they suffer, however, depends on the cause and the depth of recessions. First, the left-hand-side chart below shows the change in S&P 500 earnings per share (in blue) and the change in the real total return price for S&P 500 stocks during each of the 12 recession periods since 1948 (in gray). [11]

Company earnings have fallen in 10 of the 12 recessions—that’s about 83 percent of the time. Stocks prices, however, have behaved differently: in 50 percent of recessions since 1947, they rose despite falling economic growth and declining company earnings. Stocks don’t necessarily fall during recessions.

Source: Federal Reserve

CLICK ON CHART TO VIEW LARGER IMAGE

This surprising result is likely due to stock behavior before recessions. The right-hand-side chart above shows the change in stock prices and earnings in the six months prior to each of the 12 recessions since 1948. In these cases, stock price changes were negative 75 percent of the time. This is likely because stocks tend to fall in advance of actual economic contractions, as investors anticipate a slowdown. That is, stocks are a leading—though not always perfect—economic indicator.

Of course, eroding business conditions are bad for stocks. But sometimes the worst is over for equity prices by the time a recession is officially underway.

But rarely do they emerge from an economic slowdown unscathed. Stocks almost always retreat before or during a recession. The only exceptions to this are the relatively short and shallow recessions of 1980 and 1990, which are among the briefest downturns on record. [12]

We’ve discussed the connection between stock returns and economic growth. And we’ve seen that stocks don’t always decline during recessions; they tend to take their lumps before recessions start. The big question for equities right now is, were last year’s lumps big enough—and will any oncoming recession be mild and short enough—to insulate stocks from large losses?

Beware high valuations

While we can’t know if the U.S. economy will experience a recession in the months ahead, we can assess the potential resilience of stocks based on recent performance and “valuations,” or the price of stocks relative to their earnings.

Starting with recent performance, in the 12 months up to April 1, 2023, the total return on stocks was negative 7.7 percent. So stocks have indeed taken some lumps in the last year. Are those lumps sufficient to protect equities from further losses?

We answer this question using a measure of how expensive stocks are relative to long-term, real, smoothed earnings. The “cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio” or “CAPE” is a compact way of summarizing how cheap or expensive stocks are: the higher the ratio, the more expensive stocks are relative to their modern-era average (starting in 1980) of about 26. Today, CAPE sits at around 30.

Stocks are therefore no bargain, historically speaking. While they’ve stumbled in the last 12 months, high valuations could make them vulnerable to further losses should economic growth falter.

Newsletter endnotes:

1 https://www.cnbc.com/2023/04/18/public-pessimism-on-the-economy-hits-a-new-high-cnbc-survey-shows.html

2 Economic data referenced in this newsletter was retrieved from the St. Louis Federal Reserve online database (FRED)

3 Financial market data (capital market returns) referenced in this newsletter was retrieved from YCharts.

4 CME Fed Watch Tool

5 Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond

6 All home price and other economic data cited in this article comes from the St. Louis Federal Reserve online database.

7 June 2022. What Drove Home Price Growth and Can it Continue? FreddieMac Research Note. https://www.freddiemac.com/research/insight/20220609-what-drove-home-price-growth-and-can-it-continue

8 February 2023. Is the end of remote work jobs approaching? Forbes Magazine. https://www.forbes.com/sites/glebtsipursky/2023/02/06/the-future-of-remote-work-is-here-to-stay/?sh=189cb4da5cc9

9 AAG calculations.

10 Source: Robert Shiller data and AAG calculations.

11 Ibid.

12 Source: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Delivered to your inbox.

We aim to release two newsletters a month, one focused on financial planning and another on investing. If you are interested in having our monthly newsletters delivered directly to your email inbox, choose what topic you prefer and submit this form. Thank you for your interest in our newsletters.

Our mailing address is:

144 Gould Street, Suite 210

Needham, MA 02494

The opinions and forecasts expressed are those of the author, and may not actually come to pass. This information is subject to change at any time, based on market and other conditions and should not be construed as a recommendation of any specific security or investment plan. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

Armstrong Advisory Group, Inc. does not offer tax or legal advice and no portion of this communication should be interpreted as legal or accounting advice. You are strongly encouraged to seek advice from qualified tax and/or legal experts regarding any tax or legal matters relevant to you.

ARMSTRONG ADVISORY GROUP, INC. – SEC REGISTERED INVESTMENT ADVISER

The information contained herein, including any expression of opinion, has been obtained from or is based upon, sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed as to accuracy or completeness. This is not intended to be an offer to buy, sell or hold or a solicitation of an offer to buy, hold or sell the securities, if any referred to herein.

All investments involve the risk of potential investment losses. An investor cannot invest directly in an index. Diversification seeks to reduce the volatility of a portfolio by investing in a variety of asset classes. Neither asset allocation nor diversification guarantees against market loss or greater or more consistent returns. Bonds are subject to interest rate risk and if sold or redeemed prior to maturity, may be subject to additional gain or loss. Armstrong Advisory does not provide any tax or legal advice; please consult with your tax and legal advisers on such matters.