Investing Newsletter 4.23

Article #1 – March 2023 economic and market update

In this article, we lay out where key economic and financial market indicators stood as of March 31, 2023 as well as explain important economic and monetary policy developments.

The economy

The health of the US economy can be summarized with three key statistics: (1) the rate of unemployment, (2) the rate of change in gross domestic product (GDP), and (3) inflation. The unemployment rate, or the proportion of the labor force out of work but looking for a job, measures how well we’re using the economy’s most important asset: human capital. The lower the unemployment rate, the better. GDP measures the total dollar value of the goods and services produced each quarter on an annualized basis. The higher GDP, the better. And inflation measures the average change in prices. The more moderate and stable, the better.

In March, we learned that unemployment remained low, and the job creation rate stayed high. The unemployment rate, 3.6%, rose slightly (+0.2%) in March because the labor force grew, but still sits around 50-year lows. At the same time, new payrolls were strong (+311,000), and initial claims for unemployment insurance were subdued, averaging 198,250. [1] While certainly good news for workers, the vigorous job market could be a sign of economic overheating: unemployment that’s lower than the economy’s “natural” rate, which is probably in the 4% to 6% range, can push up wages and prices.

While some observers were encouraged by the drop in open positions or “vacancies” by roughly 400,000 to 10.8 million, total vacancies are still more than 50% higher than before the COVID pandemic. So the drop, though welcome, was hardly suggestive of labor-market easing. And finally, GDP grew at a healthy 2.7% annual rate in the fourth quarter of 2022 and is expected to clock in at a similar clip in the first quarter of 2023.

There are currently no signs of a slowdown in the economy, so businesses have little reason to cut prices and workers little reason to temper wage demands.

It’s thus not surprising that inflation remains a problem: month-over-month, the consumer price index rose by 0.4% in February and exactly 6% over the last 12 months. You might think that this was due to energy and food prices, and this is partly true. Food—at home and away from home—rose nearly 10% over the last year, but energy’s rise, +5.2%, was lower than overall inflation. The big drivers of year-over-year price increases, in addition to food, included shelter (+8.1%) and transportation services (+14.6%) thanks in part to falling gas prices (-2%). Inflation is thus not limited to food and energy—it’s broader, more widespread, and increasingly dug in.

And this is why the Federal Reserve (the “Fed”) continues to raise interest rates (see last section). This causes problems for the banks, as we saw unfold dramatically in March. Rising rates caught banks betting on indefinitely low rates wrongfooted, resulting in highly publicized bank failures. Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank were abandoned by depositors after publicly acknowledging large losses on interest-rate sensitive assets. More widespread damage appeared to be forestalled by government action, and this elevated the spirits of equity investors.

Financial markets

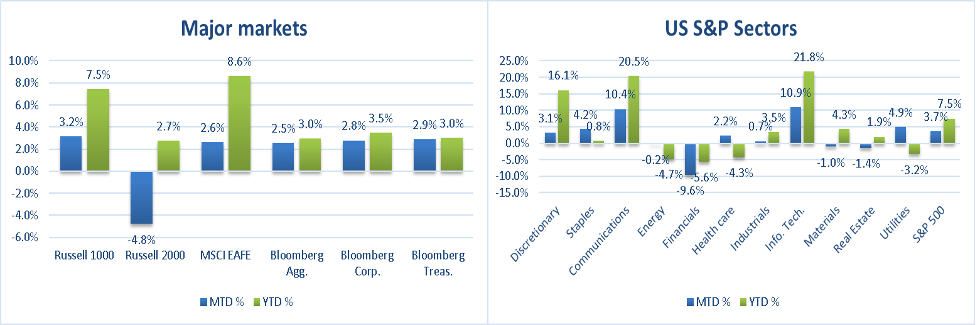

US stocks as proxied by the Russell 1000 index of US companies were the best performing major asset class in March (+3.2%)—see left chart below—followed by safe-haven US treasury bonds measured by the Bloomberg Treasury index (+2.9%). [2] Stocks benefitted from a combination of continued solid US economic performance and shrinking chances of further Fed interest-rate increases as estimated by “Fed funds futures markets”, while treasury bonds were boosted by a “flight to safety” sparked by bank turmoil as well as the possibility of lower future interest rates. High-quality (“investment grade”) corporate bonds, up 2.8% in March, were also a beneficiary of falling rates.

CLICK ON CHART TO VIEW LARGER IMAGE

Among S&P US market sectors (right chart above), information technology and communications shares, which are particularly sensitive to Fed interest-rate policy, were the best performers (+10.9% and +10.4% respectively) among the 7 of 11 S&P market sectors that posted positive returns in March. This was technology shares’ best monthly performance since July 2022. Financials, down 9.6% in March, were hit hard by banking uncertainty (see story below). Meanwhile real estate (-1.4% in March) continues to be hampered by vacancies in office properties, and now perhaps by fears of a lending crunch by increasingly skittish banks.

Economic Policy

As we were reminded in March, a bank run happens when depositors fear they won’t get their money back. This is usually because the value of a bank’s assets, which are ultimately used to pay depositors back, has declined. And bank runs can be contagious, as the early 1930s and late 2000s demonstrated. For this reason, the Federal Reserve, US Treasury, and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) took extraordinary steps to prevent the spread of bank runs in March following the failures of regional institutions Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank. These steps included insuring all deposits at failing banks. This was meant to calm depositors elsewhere, and it mostly seemed to work. Additionally, the Fed agreed to loan money to banks at 100% of the value of certain collateral at a bargain interest rate. This was meant to ensure that banks could meet depositor withdrawal demands, and it too has seemingly worked. After a few anxious days in which other regional banks came under pressure, the government’s efforts appeared to stabilize the sector: banks that, like SVB, invested record deposits in long-term bonds when their prices were high would be spared SVB’s fate.

Notwithstanding bank sector tremors, the Federal Reserve (Fed) increased its target interest rate by 0.25% to 4.75% at its scheduled meeting in late March. Fed rate hikes work by slowing demand for goods, which lowers demand for workers, which in turn takes pressure off wages and thus prices. The Fed probably had little choice to move rates higher given the persistence of inflation, despite the risk higher rates pose to weaker banks now forced to increase payouts to depositors. To soothe investor nerves, Fed Chair Jerome Powell assured investors that the Fed was mostly done raising interest rates—as a body, the Fed expects to increase rates only once more, by about 0.25%. And to cushion the blow to banks, Powell assured all bank depositors that their money is safe.

But at what cost? Deposit insurance dates to 1933 when, during the depths of the great depression, thousands of banks failed. The ceiling on FDIC insurance, currently $250,000, was intended to limit the costs of bank failure (since FDIC funds come from bank fees, and thus, indirectly, bank customers). It was also intended to impose discipline on bank investment practices: in theory, bigger depositors should insist that their banks assume unreasonable risk. In the blink of an eye, a cornerstone principle of US banking regulation was rewritten last month. Its short-term effects almost certainly stabilized banks and markets. But its long-term consequences are unknowable.

Article endnotes appear at bottom of newsletter.

Article #2 – Financial conditions

There are many measures of the state of the economy, such as GDP and unemployment (see first article). But are other, less well-known measures of economic health called “financial conditions.” Financial conditions indexes tell us about the future of the real economy as assessed by investors.

What asset prices can tell us about the future

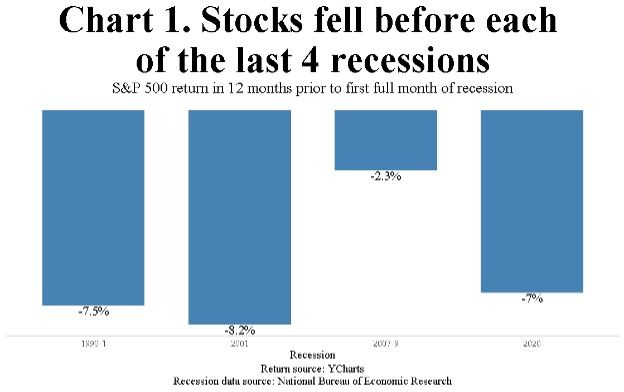

You’ve probably heard it said that the stock market is a leading economic indicator. This is because stock movements tend to foreshadow turns in the real economy. Before each of the last four recessions, for example, the S&P 500 index of leading US companies (“stocks”) declined as shown in chart 1.

But while recessions have been preceded by stock declines, not every stock decline precedes a recession. There have been some notable “false positives,” or periods during which stocks sold off that weren’t followed by a recession, such as 1987 or 2018. Despite these head fakes, stocks do a reasonable job as an early warning indicator of either recessions or slowdowns. Why is this? It’s not because investors are clairvoyant. Rather, it’s because stocks react more quickly to news about the economy than, say, surveys of consumer confidence or data on consumer spending because stocks trade continuously. Other indicators are reported far less frequently. Stocks and other asset prices are ideal leading gauges of economic health because they register changes in investor instantly.

And stocks aren’t the only security with potentially valuable information about the future. Another popular early warning indicator is the “slope” of the treasury bond yield curve, or the difference between longer and shorter-term interest rates on US treasuries. Before recessions, this slope tends to point downward because long-term rates dip below short-term rates. Both stock and bond markets therefore contain useful information about economic prospects. Other variables potentially useful for forecasting include exchange rates, commodity prices, and house prices. [3]

Financial conditions indexes

Motivated by this, researchers have created financial conditions indexes that capture a wide range of market and financial activity. The Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago (the “Chicago Fed”) specifically has created a widely followed index of over 100 financial market indicators.[3] The National Financial Conditions Index, or NFCI, consists of publicly traded securities, like stocks, bonds, and options as well as economic, financial, and banking indicators. Publicly traded securities change price every day—they’re “high frequency.” Other indicators, like bank capital and liabilities, are reported less often—they’re “lower frequency.” Together, high and low frequency data can provide a unique and valuable window on underlying economic conditions.

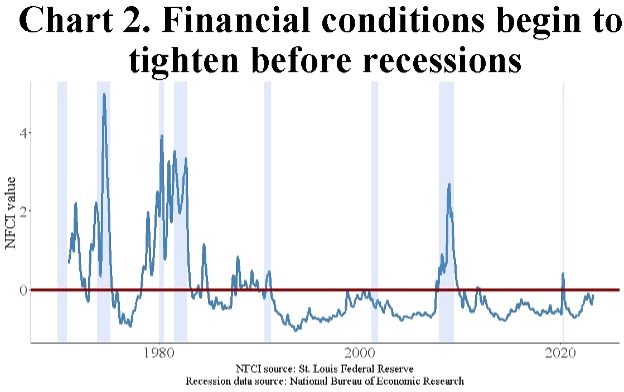

Chart 2. shows the value NFCI since 1970. Values below zero (the thick, dark red line) indicate looser-than-average financial conditions: falling interest rates, rising stock prices, expanding bank loan activity, etc. Values above zero indicate tighter-than-average conditions: rising interest rates, falling loan volumes, shaky asset prices, etc. Notice that the blue line tends to rise—financial conditions begin to get “tighter”—before recessions, which are shaded in blue. Notice also that they tend to stay elevated—that is, above the red line—throughout each recession periods, easing only toward the end of economic contractions.

While eyeballing a chart can spot potentially interesting connections, it’s not definitive evidence that financial conditions help forecast recessions. More rigorous statistical analysis has, however, shown this to be the case. [5] But it has also shown that the relationship between various financial markets and other indicators and future economic performance can change. What “worked” as a predictor in the past may not continue to work. This is unsurprising, since the structure of the economy and relationships among financial market and real economic variables like unemployment and growth are changing constantly.

What are the financial conditions telling us today?indexes

Take a look at chart 2 again. Financial conditions have “tightened” since the Federal Reserve (Fed) began raising its target interest rate in March 2022. But they remain looser than average—the blue line is below the red horizontal line drawn at zero. This suggests that capital is flowing relatively freely to borrowers, which will support continued economic growth all else equal. Normally, this wouldn’t be a concern. But with inflation still above the Fed’s 2% target—the consumer price index rose by 6% in the 12 months ending February 28—accommodative financial conditions may suggest that the Fed has yet to tighten enough to cool price pressures.

Financial conditions are a measure of the health of financial assets. As such, they can provide clues to the future direction of the economy. They tend to get tighter before recessions, and looser before and during recoveries. This makes them a potentially useful economic forecasting tool.

There are many measures of financial conditions, and indexes like the Chicago Fed’s NFCI attempt to combine them into a single, easy-to-interpret number. Currently, financial conditions are looser than average. This points to financial markets supporting economic growth and suggests that the Fed will have to continue to raise interest rates.

Article endnotes appear at bottom of newsletter.

Article #3 – Stocks and inflation

Inflation is typically bad for investment performance in the short run. It hurts bonds because it erodes the value of their fixed payments. And it can hurt stocks because it typically pushes up the interest rates used to “discount” future stock cash flows, reducing their “present value.” Inflation also creates economic uncertainty, which can cause asset prices to fall.

Although inflation may not be conducive to strong stock returns in the short run, stocks have always outperformed inflation in the long run. Investors with a long-time horizon may therefore need equities to overcome the loss in purchasing power that inflation can inflict.

Why inflation protection is important

Inflation, usually measured by the consumer price index (the “CPI”), is the rise in the average price of goods and services. In some periods, such as the early 1990s when oil prices caused the CPI to spike, this rise is brief and does no lasting damage. In other periods, like the 1970s when high government spending and money printing coincided with multiple energy and food prices shocks, inflation is prolonged and economically harmful. During the tumultuous 1970s, for example, stock prices as proxied by the Wilshire 5000 index rose about 90%. [6] But inflation rose by over 100%. [7] So, the real (after inflation) return from stocks was negative: a dollar of stocks bought about 14% less by 1980 than it did in 1970!

Since inflation reduces the purchasing power of investment returns, inflation protection is valuable. Unfortunately, investments designed to increase their income with inflation like US inflation-protected treasuries or “TIPS” (which stands for treasury inflation-protected securities) are bonds and therefore offer no long-term growth potential. At the same time, long-term investments like stocks sometimes rise when inflation rises, but sometimes fall. Because inflation protection should rise when inflation rises, so that the investor is no worse off after inflation, stocks can’t be said to effectively “hedge” inflation.

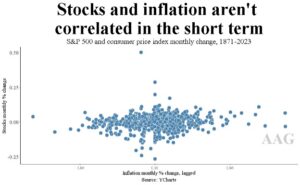

This is clear from the chart on the right, which shows the relationship between monthly stock returns – this time using the S&P 500 index of large US companies – and inflation in the prior month. If stocks effectively hedged inflation in the short-term, we’d expect the dots to point upward. But they do not.

Time makes all the difference

S&P 500 stocks (“stocks”) don’t appear to hedge month-to-month changes in the CPI. But interestingly, their inflation-hedging properties seem to improve with an investor’s holding period.

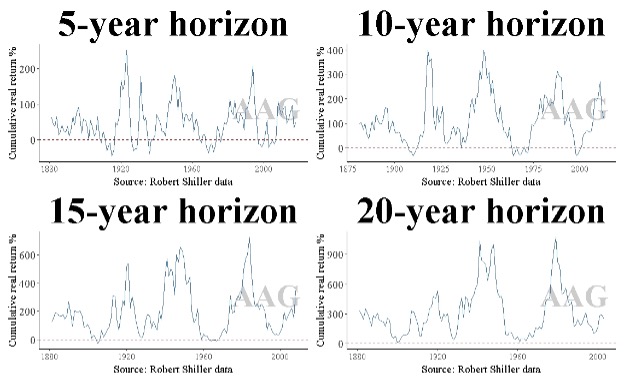

The next chart shows the total or cumulative, real (after inflation) return from stocks over rolling 5, 10, 15, and 20 periods starting in 1871. (A rolling period drops the oldest year and adds the most recent year in every calculation.) Think of each blue line as “growth of a dollar” over previous 5, 10, 15, or 20-year rolling periods.

Notice that over 5-year periods, the blue line occasionally dips below the hashed dark-red line. This means that, after inflation, stock returns were negative during that 5-year interval. This happened about 21% of the time. Notice also that as time horizon increases, the frequency of negative real stock returns declines. For 10-year periods, stocks return less than zero about 10% of the time. For 15-year periods, that becomes roughly 5% of the time. And there has never been a 20-year period in this dataset during which stock returns were negative after inflation.

Thus, while stocks aren’t a good hedge against inflation in any given year, they offered increasingly strong inflation protection as an investor’s time horizon lengthened.

For the long-term investor relying on equities for growth, this result is important. While past performance isn’t predictive and relationships among returns and economic variables like inflation can change, equities have always beaten inflation given enough time.

This shouldn’t be surprising. In the long run, most economists believe that money and inflation are “neutral”—inflation changes prices, not real economic relationships or the productive capabilities of companies or the economy. It stands to reason, therefore, that the value of a company’s assets—physical and intangible— as embodied in its stock price would adapt to inflation, which is after all just a change in prices. Both theory and evidence support the idea that stocks are a good long run inflation hedge.

Stocks may be your best bet to outpace inflation

While there’s no way to protect yourself from inflation in the short term, a broadly diversified stock portfolio such as the S&P 500 index has offered a potent defense against inflation in the long term. Unlike bonds, which provide a fixed payment (coupon interest), stocks represent ownership in companies. And inflation, which is neutral in the long run, does nothing to change a company’s long-run prospects all else equal.

Newsletter endnotes:

1 The St. Louis Federal Reserve economic database is the source of all economic data referenced in this newsletter.

2 Throughout this newsletter, S&P index data is provided by Standard & Poor’s and returns are calculated by data provider YCharts. Bloomberg index data is provided by Bloomberg and returns are calculated by data provider YCharts.

3 Stock, J. H., & Watson, M. W. (2003). Forecasting Output and Inflation: The Role of Asset Prices. Journal of Economic Literature, 41(3), 788–829.

4 The Chicago Fed’s National Financial Conditions Index consists of 105 financial indicators. https://www.chicagofed.org/research/data/nfci/about

5 Stock, J. H., & Watson, M. W. (2003). Forecasting Output and Inflation: The Role of Asset Prices. Journal of Economic Literature, 41(3), 788–829.

6 The dividend-reinvested return of the Wilshire 5000 stock index as reported by YCharts.

7 The consumer price index increased by a factor of 2.04 from 12/31/1969 to 12/31/1979. Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve Economic Database

Delivered to your inbox.

We aim to release two newsletters a month, one focused on financial planning and another on investing. If you are interested in having our monthly newsletters delivered directly to your email inbox, choose what topic you prefer and submit this form. Thank you for your interest in our newsletters.

Our mailing address is:

144 Gould Street, Suite 210

Needham, MA 02494

The opinions and forecasts expressed are those of the author, and may not actually come to pass. This information is subject to change at any time, based on market and other conditions and should not be construed as a recommendation of any specific security or investment plan. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

Armstrong Advisory Group, Inc. does not offer tax or legal advice and no portion of this communication should be interpreted as legal or accounting advice. You are strongly encouraged to seek advice from qualified tax and/or legal experts regarding any tax or legal matters relevant to you.

ARMSTRONG ADVISORY GROUP, INC. – SEC REGISTERED INVESTMENT ADVISER

The information contained herein, including any expression of opinion, has been obtained from or is based upon, sources believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed as to accuracy or completeness. This is not intended to be an offer to buy, sell or hold or a solicitation of an offer to buy, hold or sell the securities, if any referred to herein.

All investments involve the risk of potential investment losses. An investor cannot invest directly in an index. Diversification seeks to reduce the volatility of a portfolio by investing in a variety of asset classes. Neither asset allocation nor diversification guarantees against market loss or greater or more consistent returns. Bonds are subject to interest rate risk and if sold or redeemed prior to maturity, may be subject to additional gain or loss. Armstrong Advisory does not provide any tax or legal advice; please consult with your tax and legal advisers on such matters.